Historiography is the study of how history is written and interpreted. It examines historical methods, interpretations, and perspectives, shaping our understanding of the past and its evolution over time.

1.1 Definition and Scope of Historiography

Historiography refers to the systematic study of how historical events, themes, and narratives are researched, interpreted, and presented. It encompasses the methods, theories, and practices historians employ to construct coherent accounts of the past. The scope of historiography extends beyond mere chronology, delving into the analysis of sources, the role of bias, and the cultural or ideological contexts shaping historical narratives. It also explores the evolution of historical thought, revealing how different societies and scholars have perceived and recorded history over time. By examining these aspects, historiography provides a deeper understanding of how history is crafted and its relevance to contemporary debates and identities.

1.2 Importance of Historiography in Understanding History

Historiography plays a crucial role in understanding history by providing a framework for analyzing and interpreting the past. It allows historians to critically evaluate sources, identify biases, and uncover diverse perspectives, fostering a more comprehensive understanding of historical events. By examining how history has been written and interpreted over time, historiography reveals the evolution of historical thought and its connection to cultural, social, and political contexts. This discipline encourages a deeper engagement with the past, highlighting the complexities and nuances often overlooked in simplistic narratives. Ultimately, historiography enhances the accuracy and relevance of historical knowledge, making it essential for scholars and the public alike to engage with the past meaningfully.

Evolution of Historiography

Historiography has evolved from ancient to modern times, shaped by cultural, political, and intellectual contexts, reflecting changing perspectives on objectivity, interpretation, and the role of history.

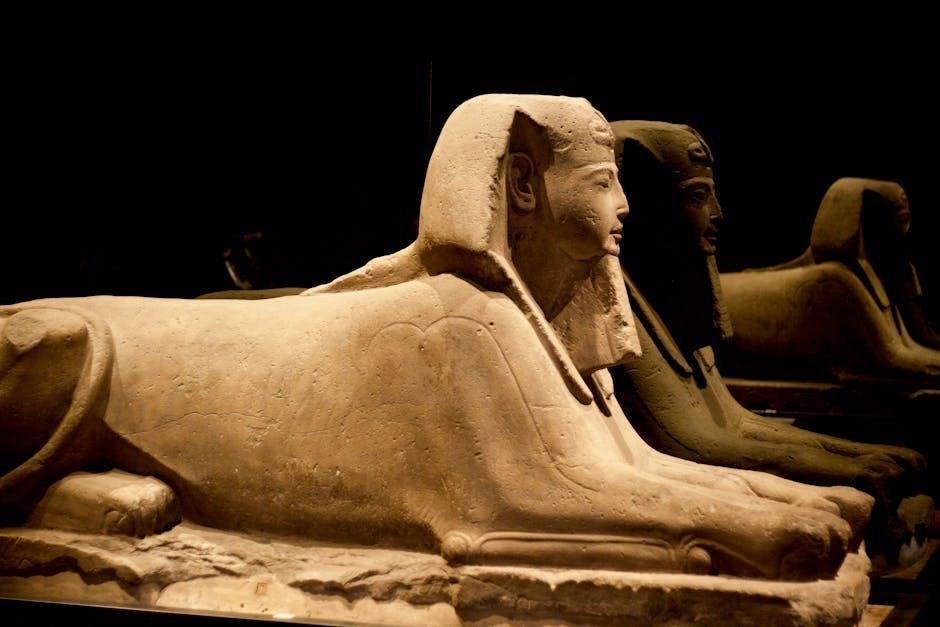

2.1 Ancient and Medieval Historiography

Ancient and medieval historiography laid the groundwork for understanding historical narratives. Early historians like Herodotus and Thucydides in Greece and Sima Qian in China pioneered systematic recording of events. Medieval historiography often intertwined religious and political agendas, with chroniclers documenting events through monastic records and royal annals. The period saw the rise of regional traditions, such as Indo-Persian and Arabic historiography, which blended cultural and religious perspectives. These early approaches emphasized moral lessons and divine providence, shaping historical accounts to serve ideological purposes rather than objective analysis. Despite limitations, they established foundational methods for interpreting the past, influencing later historiographical developments.

2.2 Modern and Contemporary Approaches to Historiography

Modern and contemporary historiography reflects a shift from traditional narratives to diverse, interdisciplinary approaches. The 20th century saw the rise of Marxist, feminist, and postcolonial perspectives, challenging Eurocentric views and emphasizing marginalized voices; Historians like Leanna Brinkley advocate for contextualizing events within broader social, political, and cultural frameworks. The Subaltern Studies Collective redefined historical inquiry by focusing on subaltern groups. Digital tools now enable innovative methods, such as data analysis and digital archiving, expanding historiographical possibilities. Contemporary approaches emphasize the role of identity, power dynamics, and global connectivity, offering a more inclusive understanding of history. This evolution underscores historiography’s adaptability to new intellectual currents and technological advancements, ensuring its relevance in the digital age.

Key Concepts in Historiography

Historiography involves analyzing historical interpretations, methods, and sources. It emphasizes understanding context, perspectives, and evidence to shape accurate and nuanced representations of the past.

3.1 Objectivity vs. Subjectivity in Historical Writing

Historical writing often grapples with the tension between objectivity and subjectivity. Objectivity refers to the ideal of presenting facts impartially, while subjectivity acknowledges the influence of personal or cultural biases. Historians strive to minimize bias by relying on credible sources and evidence-based interpretations. However, complete objectivity is challenging, as interpretations are shaped by the historian’s perspective, cultural context, and the availability of sources. Recognizing these limitations, modern historiography emphasizes transparency about assumptions and methodologies, allowing readers to critically assess interpretations. The interplay between objectivity and subjectivity remains a fundamental debate in the field, influencing how histories are constructed and understood.

3.2 The Role of Sources in Shaping Historiography

Sources are the foundation of historiography, shaping how historians interpret and reconstruct the past. Primary sources, such as archives, literary works, and oral testimonies, provide direct insights into historical events. Secondary sources, like scholarly articles and books, offer interpretations that influence historiographical trends. The availability and reliability of sources significantly impact historical narratives, as gaps or biases in evidence can lead to varying interpretations. Historians must critically evaluate sources, considering their context and limitations, to ensure accurate and balanced representations of history. The diversity of sources, from Tatar epics to Soviet-era documents, highlights the complexity of historical research and its reliance on credible evidence to inform meaningful analysis.

Historiographical Approaches

Historiographical approaches are frameworks that shape how historians interpret the past. Marxist, feminist, and postcolonial perspectives emphasize class, gender, and power dynamics, influencing historical narratives and analysis.

4.1 Marxist Historiography

Marxist historiography emphasizes class struggle and economic structures as primary drivers of historical change. It focuses on material conditions, labor relations, and the role of capitalism in shaping societies. By analyzing history through the lens of class conflict, Marxist historians aim to uncover how power dynamics and economic systems influence social and political developments. This approach critiques traditional narratives that prioritize individual agency or ideological factors over structural economic forces. Key Marxist historians, such as Eric Hobsbawm and E.P. Thompson, have explored themes like industrialization, revolution, and labor movements. Marxist historiography provides a framework for understanding history as a process shaped by collective struggles rather than elite actions, offering a critical perspective on inequality and power.

4.2 Feminist and Postcolonial Perspectives in Historiography

Feminist and postcolonial historiography challenge traditional Eurocentric narratives by emphasizing marginalized voices and experiences. Feminist historians focus on gender as a category of analysis, exploring how historical events and structures have shaped women’s lives and roles in society. Postcolonial perspectives critique colonialism’s impact, highlighting the agency and narratives of colonized peoples often excluded from mainstream histories. Both approaches aim to decenter dominant historical accounts and uncover silenced or misrepresented stories. By integrating diverse viewpoints, these methodologies enrich historiography, offering more inclusive and nuanced understandings of the past. They also encourage critical reflections on power, identity, and representation in historical writing.

Regional Historiographies

Regional historiographies explore historical writing within specific geographic and cultural contexts, reflecting diverse traditions and perspectives that shape understanding of the past in unique social settings.

5.1 European Historiography

European historiography has evolved significantly, shaped by enlightenment ideals, positivism, and Marxist interpretations. The 19th century emphasized empirical methods, while the 20th century saw diverse approaches like the Annales School, focusing on social and cultural history. European historians often explored themes of nation-building, class struggles, and intellectual movements, influencing global historical studies. Contemporary European historiography addresses multiculturalism, colonialism, and gender, reflecting a dynamic field. Its rich tradition continues to shape historical inquiry worldwide.

5.2 Asian Historiography

Asian historiography reflects diverse traditions, from ancient annals in China and Japan to Islamic and Persianate histories. Indian historiography evolved through colonial and postcolonial lenses, with the Subaltern Studies Collective challenging dominant narratives. Chinese historiography emphasized dynastic cycles and moral frameworks, while Japanese traditions blended courtly and Buddhist perspectives. Islamic historiography in regions like the Middle East and Central Asia focused on universal histories and prophetic narratives. Modern Asian historiography addresses nationalism, globalization, and cultural identity, blending indigenous and Western methodologies. This rich diversity highlights the complexity of historical writing in Asia, shaped by unique cultural, religious, and political contexts.

5.3 African and Latin American Historiographical Traditions

African and Latin American historiographies are deeply rooted in their unique cultural, social, and political contexts. African historiography often emphasizes oral traditions and communal memory, reflecting the continent’s rich pre-colonial heritage. The impact of colonialism and postcolonialism has shaped modern African historical writing, with a focus on reclaiming indigenous voices and challenging Eurocentric narratives. Latin American historiography blends indigenous, European, and African influences, with a strong emphasis on the legacies of conquest and resistance. Both traditions highlight the importance of identity, agency, and the interplay between local and global forces. These historiographies continue to evolve, incorporating diverse methodologies and perspectives to address contemporary issues and historical injustices.

The Future of Historiography in the Digital Age

The digital age is transforming historiography by offering new tools for research, analysis, and dissemination. Digital archives and big data enable historians to explore vast repositories of primary sources with unprecedented efficiency. Advanced technologies like data mining and visualization are reshaping how historical patterns and trends are identified and presented. Collaborative platforms foster global dialogue among scholars, breaking down disciplinary and geographical boundaries. Additionally, digital media democratizes access to historical knowledge, allowing diverse voices and perspectives to emerge. However, these innovations also raise questions about source reliability, digital preservation, and the ethical use of technology in historical scholarship. Balancing tradition with innovation will be key to the future of historiography.